Cite as: Dmitrij Petrov (May 2015). Introduction to the Corporate Social Responsibility, Available online, Department of Computer Science, Reutlingen University, https://dmpe.github.io/PapersAndArticles/

Introduction to the Corporate Social Responsibility

There is one and only one social responsibility of business – (…) engage in activities designed to increase its profits (…).

In the following term paper, I want to introduce my reader to them corporate social responsibility (hereby CSR). In the first chapter, I am going to deal with the understanding of the CSR and explain how we one define it, what are main theories and goals behind it and lastly show several arguments that support as well as discourage applying it. In the second part, I going to give the reader an insight into application of CSR strategy, specifically in the marketspace, work environment and community. In the final chapter, I am going to outline briefly how firms can manage social responsibility through the help of other parties (e.g. NGOs) and provide a look into the reporting as it represents results of CSR activities.

1.0. Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility

1.1. Its definition and theoretical foundation

Before I define CSR as a term, let me start with a brief look into its history. It appeared at the beginning of 20th century in the USA as corporations come under attack from their employees (e.g. social unrest related to working conditions) and communities because of being "too powerful" and engaging in "antisocial and anticompetitive practices" [Laweb13, p. 47]. Because of that, the government tried to limit firms’ power by introducing e.g. labour, antitrust and consumer-protection laws in addition to other forms of regulation (e.g. in the banking sector) [Laweb13, p. 47].

Being criticised and facing uncertain future, many great leaders such as Andrew Carnegie (the steelmaker), Henry Ford or John D. Rockefeller began using their power for volunteering their time and money for social activities becoming later great philanthropists who gave most of their wealth to charities and other foundations. These were the beginnings of corporate social responsibility initiatives [Laweb13, p. 47].

During the last century, the CSR was continuingly evolving so that in the 50s and 60s it was much more about managers being stewards [Laweb13, p. 49]. At that time, leaders saw themselves as trustees acting in the public interest. They were tasked to control vast resources (e.g. land etc.), which could easily affect other people’s lives. Thus, they had "to act with a special degree of responsibility in making" any business decisions [Laweb13, p. 49]. For example, to balance social differences they were founding charities and other social organisations helping people in need. By doing that, they were improving and further strengthening their own (and firm’s) reputation and image as well.

In the late 90s, CSR has evolved into being much more organised and carefully crafted strategy, which incorporated work of NGOs, think tanks and many other stakeholders [Laweb13, p. 59]. During second half of 20th century different terms such as business ethics, corporate citizenship or corporate social responsiveness emerged and were 'competing', yet all of them have been used to relate to the same "themes such as community, morals, and accountability" (Schwartz & Carroll, 2008) [Okpido13, p. 4]. That way, CSR "focuses on corporate self-regulation mainly associated with ethical issues, human rights, health and safety", social and environmental protection and "voluntary initiatives involving support for community projects and philanthropy" (Carroll & Shabana, 2010) [Okpido13, p. 4].

Many definitions of CSR have come out in the management and business literature, as even nowadays there are vast disagreements over the appropriate role of the corporation in society [Crane13, p. 7]. Moreover, there is also no consensus if CSR should exists in the first place at all. Crane (2013, p. 5) provides a dozen of explanations of the term based on different international organisations but to summarize all of them, social accountability tries to cover "the broad areas of responsibilities corporations have to the societies within which they operate" [Okpido13, p. 4]. In the academic literature, authors commonly talk about six core characteristics of CSR, which in the following I want to present [Crane13, p. 9].

The first one is a voluntary aspect, namely companies’ responsibility will sometimes go beyond the legal minimum; for example when the firm introduces special "easy-to-understand" calorie labelling on food and beverage items to slow down a potential governmental regulation [Crane13, p. 9f.]. The second core concept of CSR is going beyond the philanthropy, as the entire firm’s operations need "to be integrated into normal business practices rather than being left simply" to ‘additional and discretionary’ activities [Crane13, p. 9f.]. Third principle of CSR is engaging in practices and values, which are moral, ethical, fair and can underpin the business not only in social issues but also in respect to the society and the whole environment at large.

Fourth characteristic is the social and economic alignment. This asks a major question, namely how can companies be economically independent and profitable at the same time being socially responsible [Crane13, p. 11]. In fact, here firms try to balance different stakeholder interests, which (sometimes) lead to the conflict with (not only) profitability. The second to last principle is about managing externalities [Crane13, p. 10]. As an example, Crane (2013, p. 10) talks about pollution since communities bear the cost of manufacturers’ actions. In such case, the CSR needs to be voluntary as the firm should invest into technologies that prevent pollution in the first place. The last aspect of CSR, authors are often writing about, is trying to consider a range of interest and impacts among a variety of different stakeholders other than just shareholders [Crane13, p. 11]. Although there is a disagreement to what degree shareholder must be taken into account, most authors agree that prosperity of a company relies on consumers, employees, suppliers as well as other people in the community too.

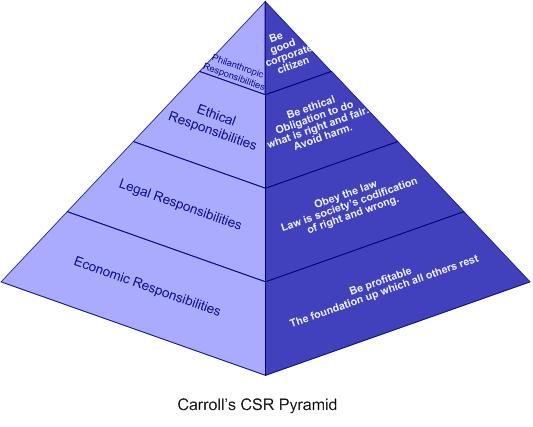

One particular explanation of CSR stands out, first defined by Archie B. Carroll in 1979, who wrote that "The social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary [philanthropic] expectations that a society has of organizations at a given point in time" [Carroll79, p. 500]. While some responsibilities are required, others are only desired and all of them are famously illustrated in Carroll’s pyramid as they "address the incentives for initiatives that are useful in identifying specific kinds of benefits that flow back to companies, as well as society" [Okpido13, p. 5].

The economic responsibility of a business is fundamental requirement to others. The company’s goal is "to produce goods and services that society desires and to sell them at a profit" (Carroll, 1979, p. 500). "Carroll claims that by doing so, businesses fulfil their primary responsibility as economic units in society" [Okpido13, p. 5]. Such principle of profit maximization is further "endorsed and amplified" by many classical economic views, led by Milton Friedman [Okpido13, p. 5]. He argued that there is only one social responsibility of business, namely "to use its resources to engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game" (i.e. without fraud) [Quote; Okpido13, p. 5]. Even though there are further differences between classical economic views "in terms of corporate profit, the notion of economic responsibility in terms of financial profit to stockholders is accepted and required" by all views [Okpido13, p. 6].

The legal responsibility of business "refers to the positive and negative obligations put on businesses by the laws and regulations of the society in which it operates" (Carroll & Shabana, 2010) [Okpido13, p. 6]. In regard to it, some authors (e.g. De Schutter, 2008) advocate expansion of legal responsibility "to encompass more regulation" as they assert that regulation "is necessary for the fulfilment of CSR" [Okpido13, p. 6]. Moreover, they "question the ability of the free market mechanism to support CSR activities" (see Valor, 2008; Williamson, Lynch-Wood, & Ramsay, 2006) [Okpido13, p. 6f.].

"In contrast, opponents of regulation argue that the free market mechanism promotes the interest of individuals, and in turn society, by rewarding CSR activities that are actually favoured by individuals" [Okpido13, p. 7]. Therefore, CSR activities that market doesn’t reward are precisely those "that individuals do not value and are therefore unwilling to support" (Carroll & Shabana, 2010) [Okpido13, p. 7].

While "economic and legal responsibilities symbolize ethical norms about fairness and justice", ethical responsibility "refers to those activities and practices that are expected or prohibited by society even though they are not codified into law" (Carroll, 1991) [Okpido13, p. 7]. In basic terms, it describes what society expects above economic and legal expectations/requirements. Carroll (1991) claims that ethical responsibility represents those standards and norms "that reflect a concern for what (…), employees, shareholders, and the community regard as fair, (…) or in keeping with the respect or protection of stakeholders’ moral rights" [Okpido13, p. 7].

Lastly, there is a philanthropic responsibility at the top of pyramid, which describes "those corporate activities that are in response to society’s expectation that businesses be good corporate citizens" – essentially promoting human welfare and goodwill (Carroll, 1991) [Okpido13, p.7; Bussoc10, p. 12]. Carroll (1991) explains that financial contributions or executive time to the arts, education or the community can be regarded as a philanthropy because it has neither ethical nor legal basis. The difference between philanthropy and ethical responsibility is that the first one "is not expected in an ethical or moral sense" [Okpido13, p. 7]. Hence, philanthropy is voluntary for businesses, yet on the other hand, "there is always the societal expectation [desire] that businesses provide it" (Okpido13, p. 7].

1.2. The business case for and against CSR

Now that the reader understands what CSR means and what its core concepts are, one can look at benefits and costs associated with it. However, before I go further it needs to be said that CSR is one of those terms, which are heavily dependent on external factors and environments, e.g. the country businesses are in. In fact, CSR in Japan and Germany will always mean something different (and thus have different arguments) because the notion of 'responsible firm' is unique to country’s historical, cultural and societal development.

The first argument supporting CSR projects is the fact that it may discourage governmental regulation in the marketplace. In fact, when business voluntary act in support of social good (e.g. pasteurizing fresh juice drinks to increase safety of products) it may head off potential introduction of a new law, which would be costly and restrict flexibility of the business [Laweb13, p. 51]. Therefore, not only the company is "accomplishing a public good" but also "its own private good" [Laweb13, p. 51].

The second argument begins where the last one ended, namely due to "accomplishing a public good", CSR promotes (long-term) other benefits for businesses too [Laweb13, p. 51]. Basically, it is in "business’s long-term self-interest to be socially responsible" (Carroll & Shabana, 2010) [Okpido13, p. 8]. Here, the reader can image a situation where the firm donates money to universities. On the one side, it can be very costly and don’t provide any clear return on investment (critics’ argument). On the other hand, the company can benefit from students who are more qualified as well as from the results of research the university achieves [Laweb13, p. 51]. Indeed, studies have shown that CSR "provides measurable benefits to businesses" (Kurucz, Barry, & Wheeler, 2008) [Okpido13, p. 8].

The third argument supporting CSR activities is about increasing firm’s valuation and its reputation too [see Petrov15; Laweb13, p. 52]. Here, reputation "refers to desirable or undesirable qualities associated with an organisation" and it is a very valuable intangible asset" that "helps to attract and retain better employees" and customers as well [Laweb13, p. 52]. By being socially responsible, the company attracts better people, which could result into further strengthening its position in the market.

The last argument supporting CSR I want to bring up is that sometimes, social responsibility can even 'correct' mistakes that business has made (or at least try). For example, after ecological catastrophes oil businesses wanting to improve their public relationship (i.e. image etc.) start to voluntary CSR initiatives such as giving funds to ecological organisations. Thus, they 'compensate' for the harm they have caused, yet on the other hand, they need to make sure that disasters won’t happen in the first place. Not coincidently, it is argued for bigger regulation in such fields as it affects the whole planet.

Although there are many arguments in support of CSR, there is also equal number of arguments, which are against CSR. Probably the biggest one is the notion that it lowers economic efficiency and firm’s profit. As a matter of fact, there is clearly a conflict. On the one hand, CSR can bring more revenue in the longer term; yet, on the other hand, it forces the company to use its resources now and by that risking its position in the marketplace. As an example, Lawrence et al. (2013) talk about an unproductive factory, which won’t be closed due to negative social effect it would have in the community [p. 53]. As a result, the firm (and its shareholders) may financially suffer and risk its future growth.

The second argument is also closely related to the first one, as the firm (engaging in CSR) bears additional costs compared to its competitors that do not. Therefore, it is putting itself in the competitive disadvantage meaning that the "competition cannot be equal" for both of them [Laweb13, p. 54]. This needs to be seen also from the global perspective, namely those companies, which only obey required law, can benefit against other CSR-active companies that go beyond the law. For example, due to lower costs.

In addition to that, although CSR can be viewed as easy task (in the rhetoric 'just give the money away'), in fact it requires special skills that business leaders may lack. Lawrence et al. (2013, p. 54) report that "putting businesspeople in charge of solving social problems may lead to unnecessarily expensive and poorly conceived approaches". As a result, although there may be an excellent CSR strategy, it is much harder to implement it in an effective way so that it can really addresses social issues. Here, also opponents of CSR argue that it is not the business leaders who should be tasked to address them, but rather politicians who have the mandate ('being elected') to even solve them [Laweb13, p. 54].

The fourth and last argument I want to mention here is a combination of two smaller ones. Not only CSR imposes 'hidden' costs on society, but mainly, it places responsibility on companies instead of individuals (of that company). Everybody understands that if a firm decides to make its products much safer, then it may try to recover associated costs in some other way. For example, by either increasing the price of the product (customers don’t want) or paying lower wages (employees don’t want).

Concerning the second argument, some authors argue that the responsibility should be placed on individual business leaders instead on the company as a whole – and they support that by the (misunderstood) example of The Giving Pledge where billionaires (not companies) promise to give away most of the wealth to solve social issues [Laweb13, p. 54f.]

1.3. Summary

To summarize the first part of this paper, the reader should already understand that CSR’s goal is to operate firm’s operations in a more responsible way by trying to manage shareholders’ as well as stakeholders’ (e.g. government) expectations, at the same time. Under CSR, companies need to "adopt standards of accountability, transparency, and sustainability", because it can differentiate them, further improve their image and profitability and finally attempt to solve some problems caused by their past decisions, having an impact on the whole community and society [CSR15, Tiwari11].

Speaking very broadly, CSR wants that business leaders take not only business responsibility but also the responsibility to protect and improve welfare of society beyond the one required by law or regulations. Hence, by doing correct 'thing', leaders contribute to social, environmental and economic goals by sharing interests of both shareholders and stakeholders [Tiwari11].

2.0. Application of CSR

2.1. Implementation of a strategy

Defining CSR strategy in the company doesn’t mean that it will be applied and executed on real issues. The problem of execution – as in any other business field – is important to consider from the beginning. Consequently, the question of how corporations actually implement their social responsibility programs cannot be more important nowadays, as even countries such Brazil, China or India are slowly embracing responsibility practises [Crane13, p. 211].

There are many ways of how successfully implement corporate responsibility in any firm regardless its size, revenue or position in the market. In fact, e.g. Hohnen (2007) wrote an implementation framework of CSR strategy, where he lists many steps that as a result may benefit society at large. In my focus, I want to examine only six steps that are described by Thorne et al. (2010) and those need to be seen from broader stakeholder’s perspective on CSR.

The first one is about conducting an assessment of the organisation and its whole culture [Bussoc10, p. 62; Hohnen07]. In fact, if CSR programs don’t align with firm’s culture, then employees won’t actively engage and understand the shared benefit to the firm and community they target. Therefore, the purpose of this is to find and identify firm’s "mission, values and norms that are likely to have implications for social responsibility" and are "deemed most important by the organisation" and its stakeholders [Bussoc10, p. 63].

The second step is now to engage different stakeholders groups that are important because of their needs (e.g. community), wants (e.g. parents) and desires (e.g. students) [Bussoc10, p. 63]. Yet, not all stakeholders can be considered equally important and vital, even though because of decision-making processes some of them may be negatively affected [p. 64]. Indeed once there is an agreement, collaboration or confrontation, all of them present their case to the public in the media, which may seriously harm as well as significantly improve firm’s reputation and image.

Hence, correct assessment of their power and legitimacy is necessary to understand "degree of urgency in addressing their needs" [Bussoc10, p. 64]. The third step deals with deep understanding of "the nature of the main issues of concern" [p. 64]. As an example, Thorne et al. (2010) mention obesity of children, where companies such as Kraft Foods or Nestle are facing many different stakeholder concerns. All of them need to be considered for building the relationship, developing ideas and new approaches with firm’s management, employees, parents, unions and many other stakeholder.

Once the first three steps have been accomplished (gathering information etc.), the fourth step is now to "arrive at an understanding of social responsibility that specifically matches the organisation interests" [Bussoc10, p. 64]. This will be used to evaluate current CSR instruments in the marketplace (i.e. ‘what does the competition’) and select concrete initiatives that contribute positively to communities where partners, customers, employees and many other groups work and live [Bussoc10, p. 64].

The fifth step deals with determination of resources and evaluation of urgency needed to accomplishment some or all CSR activities. In fact, all issues need to prioritized and assessed for the urgency, as they also might be very challenging – both capital and organisation intensive [Bussoc10, p. 64]. Therefore, having no prior experience in doing CSR, it is always recommended to start with smaller rather than bigger issues, in addition to holding frequent discussions with appropriate stakeholders for setting boundaries and consulting with them early drafts of the strategy [Hohnen07, p. 19].

The last step – according to Thorne et al. (2010, p. 65) – is about designing and implementing proposed plans and gathering stakeholder’s feedback in order to further improve started CSR activities. The plans and more importantly the commitment should be made public to build a shared trust, openness and responsibility of the firm to the promise it made in the future.

2.2. CSR in marketspace

Social responsibility in the marketspace is today one of the most important areas businesses need to engage in. In fact, by doing so they can be rewarded by gaining a premium, larger market share, new customers, attracting better employees and "building a brand that customer[s] evaluate more favourably" [Crane13, p. 213]. Take for example, an automotive industry, where today most of its brands also offer electric and hybrid cars, as their value is also heavily dependent on making cars safer and environmentally friendlier than the law requires [Crane13, p. 213]. However, we can also observe companies, which are (and most probably forever will be) in a (self-)conflict. Indeed, tobacco or alcohol companies are sometimes very irresponsible to society because of moral issues they present (their products, which they advertise, ‘kill’ people).

Because of that, the marketspace is the most important area where stakeholders "are said to act as a key drivers for CSR activities more generally", according to Crane (2013, p. 214). Customers are acting here as "a social control of business", namely if they think that the business doesn’t act ethically (enough), then they can boycott the firm (e.g. Nestle) [Crane13, p. 214]. Vice-versa, if company does more than it is required it can ‘flourish’ in the market, at least in the theory. Thus, firms "should invest in social responsibility when[ever] it is in their own ‘enlightened’ self-interest", yet in the literature there seems to be no conclusion (and neither an agreement) between an impact of social responsibility programs and further achieving business/financial success (i.e. correlation) [Crane13, p. 215].

Ultimately, some firms will benefit from CSR activities in the marketspace, while others (and Vogel ‘05 says that the most) will not [Vogel06, p. 20]. He insist that benefitting from CSR is only possible in some business areas such as oil or food industries where customers do recognize CSR values and demand them from those companies as well [Crane13, p. 215]. These two are specifically B2C markets where the public relationships and branding is also very important to customer’s buying considerations (e.g. food, apparel, tech etc.). He also list another two marketplaces, which are very important for CSR activities.

As a matter of fact, another industry, which is often under the public scrutiny, is the financial one (due to 'mistakes' it does e.g. financial crisis or "Golden parachute" payments). Not only many people depend on the having an access to their money under any circumstances even if the market crashes, Crane (2013, p. 216) reports, but also it has its own CSR field – called socially responsible investments. The author of this paper further believes that it is not necessary to explain how good financial practices could affect many social issues.

The last market, which is also deemed very important from the perspective of many stakeholders, is the B2B market where large companies such as Dell may significantly affect its supply chain and by doing that e.g. help stopping child (labour) abuse. Thus, CSR operations in such marketplaces enforce sustainable practices between businesses and indirectly enhance brand’s perception, even though customers are not actively engaged here [Crane13, p. 216].

2.3. CSR in workspace and community

Social responsibility in the workspace is one of the most problematic, complex and hard issues companies need to face every day. As already mentioned in the first chapter, it all began at the begging of 20th century when leaders recognized the responsibility and benefit it can bring them for improving working conditions for their employees (e.g. housing, health care etc.). Here definition of Carroll (1979) also applies, as companies have a clear economic (e.g. wages and benefits), legal (e.g. health and safety, sexual harassment), ethical (e.g. diversity, work/life balance) and philanthropic (e.g. voluntary participation in marathons in support of social good) responsibility towards their employees [Bussoc10, p. 248].

As written, positive treatment of employees not only improves firm’s reputation but also attracts skilled knowledge workers [Crane13, p. 253]. Furthermore, due to the improved working conditions and increased employee morale, companies should not have a problem of "transferring a culture of socially responsible behaviour [in the community] towards other stakeholders" too [Crane13, p. 253].

Yet, with rise and fall of unions, CSR has been shifted away from workers so that neither unions, nor labour laws seem to be interested in that anymore (at least in some countries) [Crane13, p. 254]. Especially in Europe (and to smaller extent in the USA), where there is too much regulation, which gives employees very broad and comprehensive legal protections, CSR activities in the working environment are left to the side for only those that are required by the law [see Siebert (2006); Crane13, p. 254].

On the other hand, CSR in communities is very much different and easier topic. Even though the leaders at begging of 20th century were improving employees’ quality of life, the benefits of managements’ actions were shared among communities as well [Crane13, p. 292]. By voluntary donating money to charities and other social organisation, companies showed their support of the neighbourhood. Due to not being able to relocate overnight, the social problems are "hard to miss" and shared with all social classes [Crane13, p. 292]. Therefore, the significant focus of CSR activities lies in the local communities as they have greater implications on businesses and can strengthen (and establish new) valuable relationships from which both sides can benefit.

In fact, communities can benefit from variety of CSR programs. Not always, it is about the money; in many cases it is also about devoting time e.g. to universities or (physically) helping poor people in needs. Such philanthropic donations are nowadays also often (sadly) viewed to be calculated actions for buying "local compliance to corporate plans, [or] (…) merely a public relations device that raises cynicism because it adds little of value to the cause, or even because it provides little real benefit to the firm (Hess et al., 2002)" [Crane13, p. 293]. Hence, many CSR programs often go under different labels as well, e.g. ‘corporate community investments’ [Crane13, p. 293].

3.0. Managing CSR programs – Reporting and the Role of 3rd parties

Implementing company’s social responsibility programs does not always present a success or failure at the end of the day. Sometimes it can also go even unnoticed and the firm consequently ‘is forced’ to inform the media/employees/governments. Moreover, it can be necessary to prove to its stakeholders that CSR activities company does have a real impact and that the firm is ‘doing the right thing’ as well [Crane13, p. 401]. Indeed managing CSR deals with many aspects of "how stakeholders actually find out whether the company has acted responsible or not" [Crane13, p. 401]. This topic about reporting and auditing is one of two, which I want to talk briefly in this chapter.

First, there are several reasons why companies not only publish their mandatory financial statements (e.g. quarter/annual reports) but prepare ‘special’ reports on their CSR activities as well, e.g. Microsoft . Some reasons are purely political, whereas others are ethical ones. Multinational companies such as Google "are perceived as increasingly powerful institutions", where power calls for more transparency, and thus the accountability [Crane13, p. 402]. In fact, the power itself and firms’ other actions in the marketplace might pose a threat to the competition, society and (possibly) environment too.

Therefore, the firm has to monitor them carefully and whenever it can, it should act in the best interest of shareholders and equally important stakeholders too (e.g. building energy-independent data centres that are less costly and help ‘save’ the planet). Many of such actions should be then reported in the company’s CSR report in order to present the broader public their taken actions for improving society, environment and world [Crane13, p. 403].

In recent years, there has been a significant undertake into standardizing (industry) unique CSR reports and provide integrated reporting guidelines, which combine both financial statements as well as CSR ones. Furthermore, regulators have been also very active and in many countries such as Japan or Denmark there are now specific policies how and what to report in regard to social accountability [Crane13, p. 404f.].

Until this chapter, I have talked exclusively about companies (and to a smaller extent individuals too) being solely responsible to the society and community at large. However, CSR activities are much more commonly associated with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other partners (e.g. think tanks) as well [Crane13, p. 488]. Firstly, NGOs can be viewed as "watchdogs ensuring that irresponsible behaviour is identified and more socially responsible alternatives promoted" [Crane13, p. 489]. Secondly, they can also play a more active role in cooperation with the firm to solve issues as it may closely relate to the argument made in previous parts of this paper that firms and their leaders may lack special skills needed to successfully implementation of CSR strategies.

4.0. Conclusion

At the begging of this paper, I sat out to explore the world of the Corporate Social Responsibility. Therefore, in this rather smaller chapter, I want to summarize main ideas and provide the reader an overview of the CSR.

As already mentioned, CSR is about incorporating sustainability into the firm’s operations so that not only businesses themselves but also their employees, customers, communities and the whole environment could benefit from fair and "right-doing" companies. Even though it can sometimes also bring some negative aspects (e.g. costs or required expertise in the field), most of authors today clearly conclude that advantages overweight disadvantages.

The CSR is today becoming even more significant due to financial and political crises, which happen unexpectedly around the world and have broader and profound impacts on many individuals, not only for rich or poor. Therefore, the responsibility shouldn’t be seen today as an additional activity but rather businesses should embrace it fully and contribute maximum back to the society.

| [Bussoc10] | McAlister, Debbie Thorne, O. C. Ferrell, and Linda Ferrell. “Business and Society: A Strategic Approach to Social Responsibility.” Cengage Learning, Jan. 2010. Web. 24 Mar. 2015. http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/business-and-society-debbie-thorne-mcalister/1100964080?ean=978143904231 |

| [Carroll10] | Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12 (1), 85–105. |

| [Carroll79] | Carroll, Archie B. "A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance." Academy of management review 4.4 (1979): 497-505. |

| [Crane13] | Crane, Andrew. “Corporate Social Responsibility: Readings and Cases in a Global Context.” Better Planet Books. Routledge; 2 Edition (July 23, 2013), n.d. Web. 05 May 2015. http://www.betterplanetbooks.com/Corporate-Social-Responsibility-Readings-and-Cases-in-a-Global-Context-by-Andrew-Crane_p_408989.html |

| [CSR15] | “Corporate Social Responsibility.” N.p., n.d. Web. 05 May 2015 http://www.metricstream.com/solutions/corporate_social_responsibility.htm |

| [Hess02] | Hess, David, Nikolai Rogovsky, and Thomas W. Dunfee. “The next wave of corporate community involvement: Corporate social initiatives.” California Management Review 44.2 (2002): 110-125. |

| [Hohnen07] | Hohnen, Paul. “Corporate Social Responsibility: An Implementation Guide for Business.” Ed. Jason Potts. International Institute for Sustainable Development. 978-1-895536-97-3, 2007. Web. 05 May 2015 |

| [Kurucz08] | Kurucz, E., Barry, C., & Wheeler, D. (2008). Chapter 4: The business case for corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 83–112). Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [Laweb13] | Lawrence, Anne, and James Weber. “Business and Society: Stakeholders, Ethics, Public Policy.” McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 14 Edition (February 25, 2013), n.d. Web. 05 May 2015.http://www.amazon.com/Business-Society-Stakeholders-Ethics-Edition/dp/0078029473 |

| [Okpido13] | Okpara, John, and Samuel O. Idowu. “Corporate Social Responsibility: Challenges, Opportunities and Strategies for 21st Century Leaders.” Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. Print. 05 May 2015 https://books.google.de/books?id=6wu7BAAAQBAJ |

| [Petrov15] | Dmitrij Petrov (Feb. 2015). Business Valuation: Estimating Fair Value of Companies on the Example of Adobe Systems Inc., Available online, Department of Computer Science, Reutlingen University, https://dmpe.github.io/PapersAndArticles/ |

| [Quote] | Friedman, Milton. “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, by Milton Friedman.” The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970, 13 Sept. 1970. Web. 02 May 2015 http://www.colorado.edu/studentgroups/libertarians/issues/friedman-soc-resp-business.html |

| [Schutter08] | De Schutter, O. (2008). Corporate social responsibility European style. European Law Journal, 14, 203–236. |

| [Schwarz08] | Schwartz, M., & Carroll, A. B. (2008). Integrating and unifying competing and complimentary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Business and Society, 47, 148–186. |

| [Siebert06] | Siebert, W. Stanley, 2006. “Labour Market Regulation in the EU-15: Causes and Consequences – A Survey”, IZA Discussion Papers 2430, Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA). https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp2430.html |

| [Tiwari11] | Saurabh Tiwari, Corporate Social Responsibility, 1 Dec. 2011, Web. 05 May 2015 http://www.slideshare.net/tiwrsaurabh/csr-ppt-10418775 |

| [Valor08] | Valor, C. (2008). Can consumers buy responsibly? Analysis and solutions for market failures. Journal of Consumer Policy, 31, 315–326. |

| [Vogel06] | Vogel, David. “The Market for Virtue: The Potential And Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility.” Brookings Institution Press, Aug. 2006. Web. 05 May 2015. http://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=e7uk29lkoHgC |

| [Will06] | Williamson, D., Lynch-Wood, G., & Ramsay, J. (2006). Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 317–330. |

| [Pyramid] | http://www.csrquest.net/imagefiles/CSR%20Pyramid.jpg |